Why I'm Not Acting On A 2023 Recession (Could, Will, In)

I’ve noticed financial influencers are confident that there will be a recession ‘In’ 2023. In response, many are selling everything and planning to buy back at the bottom. But I would caution against acting on this thesis. It sounds plausible (and plausible mistakes are the most dangerous ones), but

Could, Will, and In

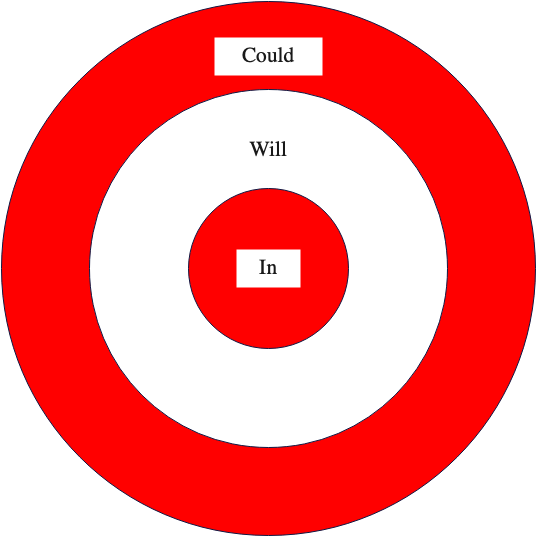

In the finance industry, an “investment thesis” is an argument supporting an investment. From my observations, there are three kinds of investment theses. I categorize them as ‘Could’, ‘Will’, and ‘In’.

‘Could’ theses examine a range of possibilities. An example: “Tesla could become the number one car company in the world. However, their competition could also compete well and make them just another EV company among many.”

‘Will’ theses zoom in on a specific event, ignoring all other possibilities. An example: “Tesla will become the number one car company in the world.”

‘In’ theses are those that are certain about a specific event AND its timing. An example: “Tesla will become the number one car company in the world in 2025.”

Observe that the latter is always contained within the former. ‘In’-s make up ‘Will’-s make up ‘Could’-s. If we put them in a Venn diagram, it would look like a shooting target:

Why ‘Could’ Theses Are Superior

‘Could’ theses are superior because they account for a wider range of events.

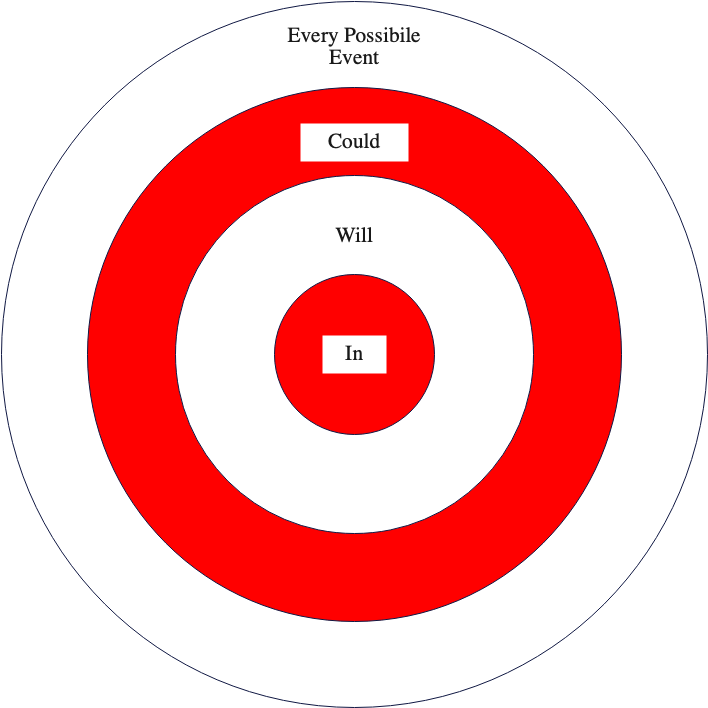

Every investment thesis is just a model. In reality, there are far more possible events than you can account for. (To prove this, just try looking for an investment thesis that predicted COVID and the Ukraine war before 2020. I doubt they exist.)

We can visualize how reality relates to our theses by adding another layer to our Venn diagram:

Since it's impossible to list every potential future event, the best we can do is to prepare for a wide number of scenarios. This is what ‘Could’ theses allow us to do.

Contrast this with ‘In’ theses, where an exact series of events needs to happen within a specified timeframe. Predicting many variables with bulls-eye accuracy is incredibly hard – even when it seems like you’re obviously correct.

Just ask the hedge funds who shorted Gamestop because they believed it would crash ‘In’ a few weeks: They were correct about it being an overpriced company, but they were wrong about how long retail investors could continue to hype up its stock price. These funds lost billions of dollars as a result. [1] To quote Keynes: “Markets can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent”.

Using the shooting target diagram above: “Every Possible Event” represents the entire area where an arrow could land. Our goal is to make sure the arrow lands in our space. So we use ‘Could’ theses to cover as much space as possible.

A Recession 'In' 2023?

I’ve noticed financial influencers are confident that there will be a recession ‘In’ 2023. In response, many are selling everything and planning to buy back at the bottom.

But I would caution against acting on this thesis. It sounds plausible (and plausible mistakes are the most dangerous ones), but there are many other ways that 2023 can unfold.

Analyzing this “wait for the bottom” strategy, you’ll find that it consists of 3 conditions:

- A recession must happen in 2023.

- The recession must cause stock prices to fall.

- You must have the ability to buy the market bottom after the first 2 conditions are met.

Let’s try zooming out from this ‘In’ thesis and checking its ‘Could’ alternatives.

- The deep recession could be delayed, just like the 2022 dip the world had been expecting – since 2019 [2].

- Markets could go upwards unexpectedly. After all, who was expecting COVID to lead to a bull market over the past 2 years?

- Perhaps a recession could happen, but maybe these expectations are already priced in the markets. Downward price movement only happens when things are worse than expected, after all.

- Maybe a recession would happen, and stock prices would fall – but you’d fail to time the bottom. (This is overwhelmingly likely, by the way [3]).

You need to hit a financial bull’s eye to make this strategy worth your while. And if you’re wrong, you risk losing out on potential dividends and upward price movements.

The largest increases in the stock market tend to happen during recoveries from massive drops. Missing just 10 of the best days in a given decade can decrease your earnings by more than 50%. [3]

Remember: unexpected events are not always negative. Some are profitable as well, and staying invested exposes us to serendipity.

If you stay invested, you might not be able to time the bottom, but at least you’re more certain to make an adequate amount of money.

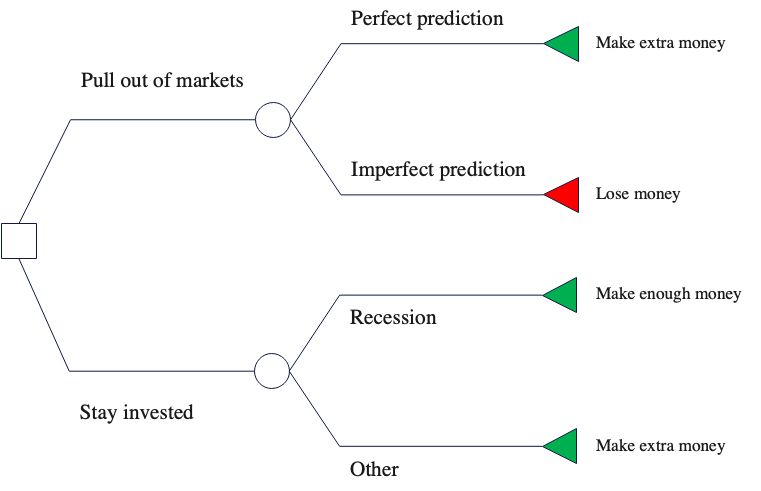

If we mapped out the choice between staying invested and pulling out of the markets, it would look like this:

Since staying invested leads to good outcomes either way, I think it’s the better decision.

If you see a 50% sale from a store that rarely gives bargains, will you delay buying because you think a 70% discount will happen ‘In’ the next year?

Knowing that such a discount ‘Could’ also never come again, it would make more sense to lock in the discount and buy now.

References

[1] https://www.wsj.com/articles/melvin-plotkin-gamestop-losses-memestock-11643381321