Some Cheap Stocks Are Traps. Use The "Secondhand Rule" To Protect Yourself.

A common investing mistake is buying every company that looks cheap. Just because a company is priced at a 50% discount to your valuation does NOT mean you should immediately buy! What should you do instead?

The most common mistake new Value Investors make

Value investing is all about finding out what a company is worth and buying at a discount to this "fair value".

A common mistake new value investors make is buying every company that looks cheap according to their valuation techniques. However, this can be dangerous because cheap companies usually have real problems behind them: Maybe profits are trending down. Maybe it's in a dying industry. Maybe it's currently under threat of bankruptcy.

Just because a company is priced at a 50% discount to your valuation does NOT mean you should immediately buy!

What should you do instead? That's where the Secondhand Rule comes in.

The Secondhand Rule

Let's say you're trying to buy an expensive secondhand item. Maybe it's a car, a computer, or even a house.

You inquire about the selling price and are told that it's extremely cheap - just 30% of the regular secondhand rate!

You'd probably have a lot of questions: Why are they selling it? Is it damaged? Can they guarantee its authenticity?

There are many things you might do, but one thing is for sure: You will NOT buy until these questions are answered.

This analogy translates to buying stocks. I like to call this concept the Secondhand Rule:

The Secondhand Rule:

Before investing in a cheap company, you must fully inspect it for defects and downsides.

How can we apply this principle? Just like a thorough inspection of a cheap secondhand item, there are quantitative metrics and qualitative information that we can use to test the health of a company from different angles.

Three sample metrics to help you find red flags

Note: These items can be phrased differently depending on the company's accounting conventions. For instance: "Operating Cashflow" might be listed as "Cash Flow from Operations". When in doubt, Google is your friend.

Income/Profit and Revenue Growth

Watch out for: Yearly decreasing values of Income/Profit and Revenues.

You can find the Income/Profit and Revenue line items in the company's Income Statement.

Checking how these change throughout the years is important because you don't want to buy into a sinking company.

If you see a cheap company that has consistently been losing profits and revenue over time, it's possible that this lousy performance has already been accounted for by the company's low market price.

Total Operating Cashflow

Watch out for: Very low or negative Operating Cashflows.

You can find the Total Operating Cashflow line item in the company's Cash Flow Statement.

Operating cashflows tell you how much cash is generated from normal business activities, as opposed to the cash raised through non-operations activities such as raising debt.

Cashflows are only loosely related to profits. For example: If a company sells everything on credit and does a terrible job collecting what their customers owe, then they'll have profits, but they won't have any cash!

Operating cashflows are important because they tell you whether a company makes cash with its regular business. If a company only generates cash through investing and financing activities, then it's heavily reliant on third parties to stay afloat.

Debt/Equity Ratio

Watch out for: Debt/Equity Ratio near and above 1

To get a company's Debt/Equity Ratio (D/E Ratio), divide its Total Liabilities by its Total Equity. Both these line items can be found in the company's Balance Sheet.

The D/E Ratio tells us how heavy the debt of the company is. A high D/E Ratio means that the company has a lot of debt relative to its size.

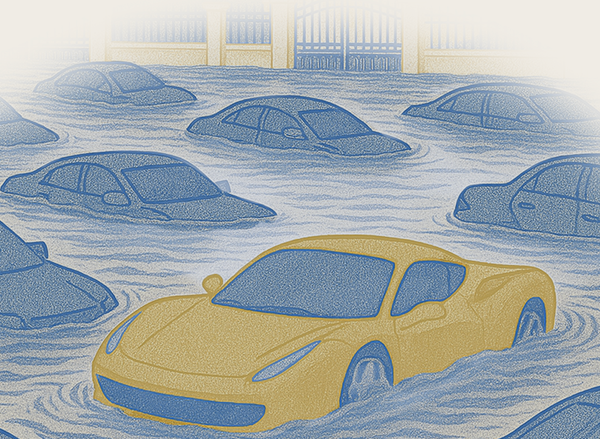

Knowing how much debt a company has is important because in the event that a company cannot pay its debts, it can go bankrupt. An ideal company would have no debt, but personally, I'm comfortable with D/E ratios at around 1 or less.

Note that there are scenarios and industries where a higher D/E ratio is acceptable. For instance, there are real estate companies with enough real estate assets to pay off all their debts, even if their D/E ratios are above 1.

Conclusion

The Secondhand Rule states: "Before investing in a cheap company, you must check if anything is wrong with it."

By using the Secondhand Rule, you can avoid buying into "value traps" - companies that look cheap, but are actually fairly valued or even expensive due to their terrible performance.

Following this rule and inspecting your investments for possible blind spots will help you avoid losses and keep your capital intact.